Progress in Modeling Cardiac Myocyte Calcium Cycling and Investigating Arrhythmia Mechanisms: A Study Focused on the Ryanodine Receptor

-

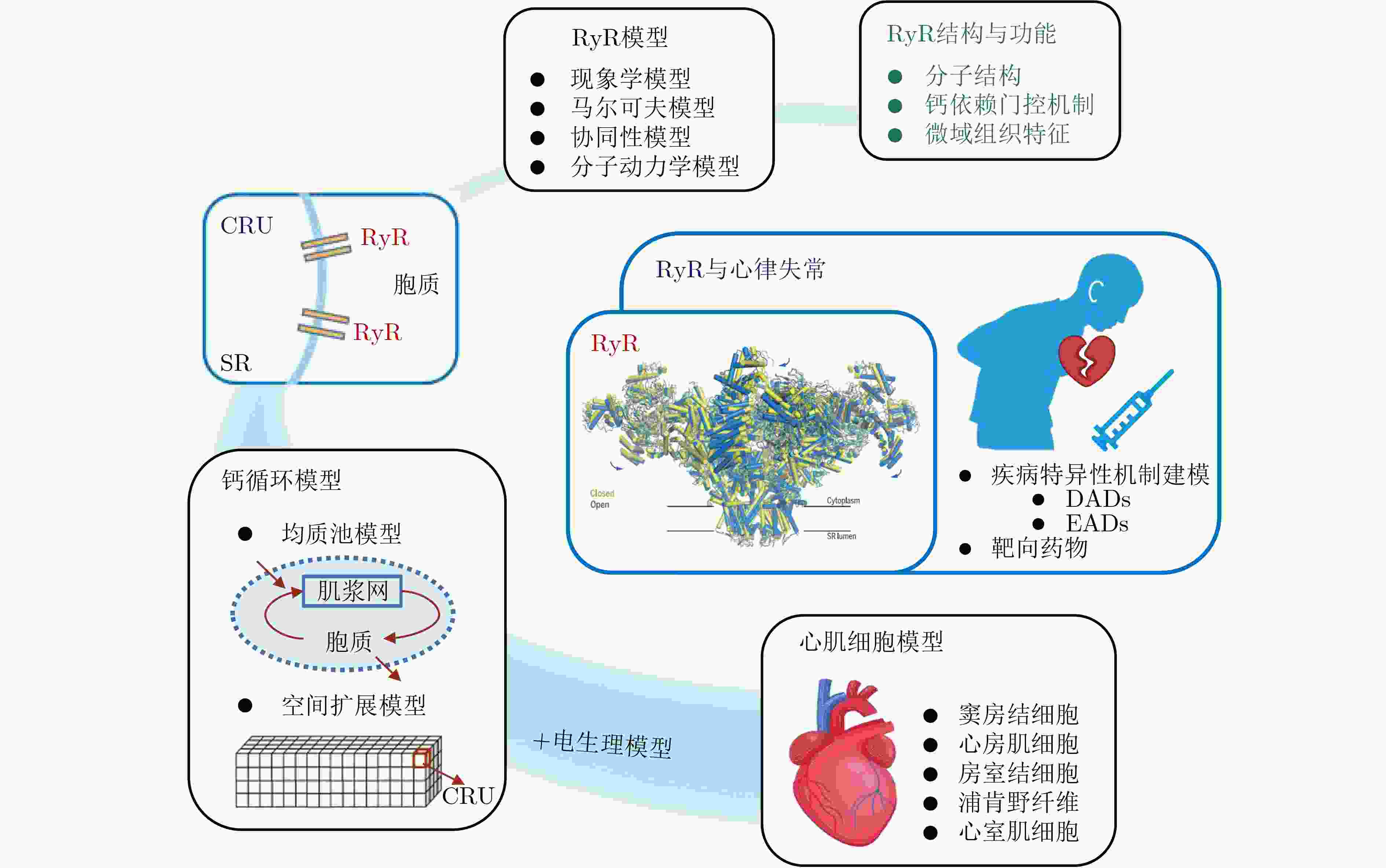

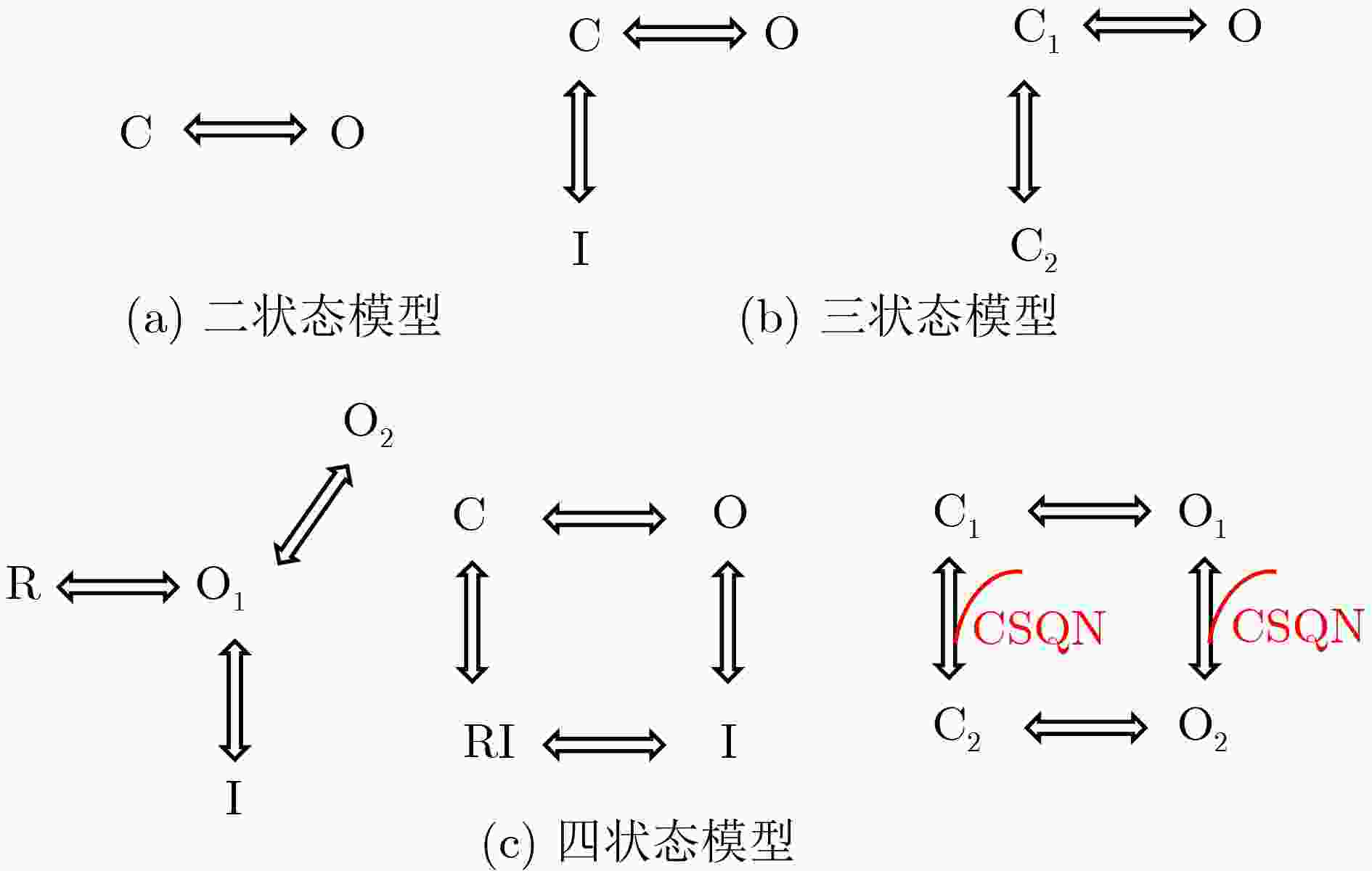

摘要: 雷诺定受体(RyR)是调控心肌细胞钙稳态的关键蛋白,主要介导肌浆网的钙离子释放。RyR的功能异常,无论是过度激活还是功能减弱,均可触发异常钙释放,诱发早期后去极化(EADs)和/或延迟后去极化(DADs),这是心律失常发生和发展的重要机制。为深入探究RyR在生理及病理状态下的行为特性,研究者已开发并广泛应用多种融合其随机门控特性的数学与计算模型。本文系统梳理了RyR的结构特征和关键生理功能,重点归纳了其建模策略,总结了RyR模型在心肌细胞钙循环模型中的整合研究进展及其在不同类型心肌细胞中的应用,并深入剖析了RyR功能异常介导心律失常的机制及其靶向药物的研发现状。进一步地,本文讨论了人工智能(AI)、数字孪生等新兴方法在 RyR 建模中的潜在作用,并对现有模型的适用性与发展方向进行了展望。Abstract:

Significance Ryanodine receptor (RyR) is an essential regulator of cardiac intracellular calcium homeostasis by controlling the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Its functional abnormalities, such as overactivation or impaired activity, are critical mechanisms underlying early and delayed afterdepolarizations, significantly increasing the risk of arrhythmias. The dynamic coupling between electrical activity and calcium cycling in cardiomyocytes involves highly dynamic and spatially organized processes that are challenging to fully capture experimentally. Conventional experimental techniques, such as animal models and pharmacological studies, are limited by high costs and difficulties in controlling variables. As a result, developing mathematical models and computer simulations of the RyR has become a crucial approach for investigating RyR function regulation under physiological and pathological conditions, as well as its arrhythmogenic mechanisms. This review provides a systematic overview of RyR biology and modeling. It begins by synthesizing RyR structural features and fundamental functional properties to establish a mechanistic basis for gating and regulation. Next, it evaluates contemporary and emerging modeling techniques, outlining the merits and limitations of various computational approaches. The review then summarizes the integration of RyR models into cardiac Ca2+ cycling frameworks and their applications across cardiomyocyte subtypes. Furthermore, the review covers arrhythmogenic mechanisms arising from RyR dysfunction and examines targeted drug therapies designed to normalize channel activity. Finally, it highlights artificial intelligence and cardiac digital twins as emerging paradigms for advancing RyR modeling and therapeutic applications. Progress The accumulation of RyR structural data has driven continuous innovation in modeling strategies. Early models often used phenomenological strategies that were practical but mechanistically limited. Markov models now represent the dominant computational framework for simulating RyR gating behavior, enabling detailed replication of calcium sparks and other key events through discrete state transitions. A key advantage of deterministic integration over other numerical methods for solving Markov models is its superior computational efficiency and remarkable flexibility in adapting to diverse cardiomyocyte types. However, it ignores the stochastic nature of RyR opening and fails to reproduce stochastic fluctuations in intracellular calcium concentration, potentially leading to discrepancies between simulations and physiological reality. In contrast, stochastic Markov models can capture these random behaviors, which are critical for investigating arrhythmogenic phenomena like calcium waves. However, they necessitate substantial experimental data and considerable computational resources, consequently hindering their broader-scale application. The development of artificial intelligence methods, including the use of deep neural networks to compress Markov models into single equations, has substantially improved computational efficiency. Meanwhile, structural biology advances have clarified the conformational dynamics of RyRs and subunit cooperativity in gating, especially in diastolic calcium leak, prompting more detailed models like those incorporating subunit interactions or molecular dynamics. Additionally, various RyR models have been successfully integrated into cardiac action potential frameworks, serving as powerful tools for investigating arrhythmogenic mechanisms like delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and early afterdepolarizations (EADs). These models not only enhance the understanding of electrical disturbances caused by RyR dysfunction but also provide a valuable platform for antiarrhythmic drug screening and mechanistic research. Conclusion Several RyR models have been developed that accurately simulate essential physiological processes such as calcium sparks, enabling broad application in cardiomyocyte calcium dynamics studies. However, current modeling efforts face considerable challenges:(1) Lack of a unified modeling framework. There is still no unified RyR model capable of accurately simulating calcium dynamics across the wide spectrum of physiological and pathological conditions. To select appropriate model for intracellular calcium handling, careful evaluation of the specific effects of different models is necessary. (2) Computational burden restricts multiscale integration. While multiscale models are essential to bridge arrhythmic mechanisms from cellular calcium dynamics to tissue-level propagation by incorporating heterogeneity, their high computational cost presents a formidable barrier to scaling for clinically relevant applications. (3) Underdeveloped pacemaker cell models. Existing research focuses largely on ventricular and atrial myocytes, while pacemaker cell models are relatively underdeveloped and often employ “common pool” approximations that fail to capture spatial calcium gradients. Future research should therefore prioritize the development of detailed pacemaker cell models that represent calcium release unit (CRU) networks and incorporate realistic RyR dynamics. While still in early stages of development for RyR modeling, emerging approaches like artificial intelligence and cardiac digital twins thus offer substantial potential to advance both mechanistic understanding and applications in precision medicine. Prospects The future of RyR research will increasingly rely on combining multidisciplinary advances across structural biology, biophysics, and computational science. Integrative efforts are essential to bridge molecular-scale conformational changes of RyR to organ-level cardiac function, which will enable the creation of scalable and clinically actionable models that not only deepen mechanistic insight but also accelerate translational innovation in precision cardiology. Emerging tools like AI and cardiac digital twins offer a pathway toward clinically relevant, multi-scale cardiac models that incorporate patient-specific electrophysiology and calcium handling. Such models could profoundly improve our understanding of arrhythmia mechanisms and heart failure pathophysiology, while also serving as predictive platforms for mechanism-based personalized antiarrhythmic therapy development. -

Key words:

- ryanodine receptor /

- cardiac myocyte /

- calcium cycling /

- arrhythmias

-

图 1 RyR建模策略及应用概览

图中展示的RyR结构图来自Peng等人[14]对猪心脏RyR2冷冻电镜结构解析

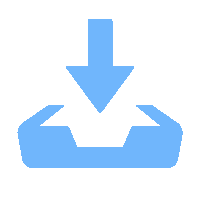

表 1 不同类型的RyR模型

模型类别 代表方案 核心思想 主要优势 主要局限 代表模型 现象学模型 经验公式模型 根据观测拟合经验关系 简单/易耦合 机制解释性弱 Luo-Rudy模型[46] HH范式模型 门控变量表征激活/失活 直观关联CICR机制 未涵盖多态转换 Chudin模型[49] 统计火花模型 以Ca火花统计分布建模 参数可测 难以扩展研究 Shiferaw模型[50] 马尔可夫模型 二状态模型 仅含“开/关”状态 结构简单 无适应/失活 Cannell模型[51] 三状态模型 引入适应态或新关闭态 可模拟不应期 多重调控刻画弱 Hinch模型[52]、Greene-Shiferaw模型[53] 四状态模型 包含多个状态 生理适配性强 参数多且依赖特定条件 Keizer模型[54]、Stern模型[55]、Restrepo模型[56] 亚基间协

同性模型Monod-Wyman-Changeux模型 亚基结合改变整体构象 机制清晰、参数简洁 无法模拟亚基异步

的状态转换Zahradnikova模型[57] 基于马尔可夫框架

的模型各亚基独立变化,

通过能量矩阵量化协同灵活性强、物理直观 计算复杂度高 Wang模型[58]、Greene模型[59] 分子动力学模型 - 基于冷冻电镜结构

进行全原子模拟分辨率高、靶向精准 计算成本极高 Greene模型[60]、Dal Cortivo模型[61] -

[1] STEINBERG C, ROSTON T M, VAN DER WERF C, et al. RYR2-ryanodinopathies: From calcium overload to calcium deficiency[J]. Europace, 2023, 25(6): euad156. doi: 10.1093/europace/euad156. [2] BADDELEY D, JAYASINGHE I, LAM L, et al. Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(52): 22275–22280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908971106. [3] 柏树令, 应大君, 丁文龙, 等. 系统解剖学[M]. 8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2013: 186–203.BAI Shuling, YING Dajun, DING Wenlong, et al. Systematic Anatomy[M]. 8th ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2013: 186–203. [4] AKSENTIJEVIC D, SEDEJ S, FAUCONNIER J, et al. Mechano-energetic uncoupling in heart failure[J]. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 2025, 22(10): 773–797. doi: 10.1038/s41569-025-01167-6. [5] MANOJ P, KIM J A, KIM S, et al. Sinus node dysfunction: Current understanding and future directions[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2023, 324(3): H259–H278. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00618.2022. [6] GUO Shuang, HU Yingqing, LING Li, et al. Molecular mechanisms and intervention approaches of heart failure (review)[J]. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2025, 56(2): 125. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2025.5566. [7] MIOTTO M C, REIKEN S, WRONSKA A, et al. Structural basis for ryanodine receptor type 2 leak in heart failure and arrhythmogenic disorders[J]. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1): 8080. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-51791-y. [8] PAUDEL R, JAFRI M S, and ULLAH A. Gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations in the RyR2-expressing gene are responsible for the CPVT1-related arrhythmogenic activities in the heart[J]. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 2024, 46(11): 12886–12910. doi: 10.3390/cimb46110767. [9] KOVALEV I A, SOLOVIOV V M, BEREZNITSKAYA V V, et al. Calcium release deficiency syndrome, a rare variant of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia[J]. Pediatria. Journal Named After G. N. Speransky, 2023, 102(6): 195–201. doi: 10.24110/0031-403X-2023-102-6-195-201. [10] PORRETTA A P, PRUVOT E, and BHUIYAN Z A. Calcium release deficiency syndrome (CRDS): Rethinking “atypical” catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia[J]. Cardiogenetics, 2024, 14(4): 211–220. doi: 10.3390/cardiogenetics14040017. [11] ZHANG Yadan, SEIDEL M, RABESAHALA DE MERITENS C, et al. Disparate molecular mechanisms in cardiac ryanodine receptor channelopathies[J]. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2024, 11: 1505698. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2024.1505698. [12] GONANO L A, KINNS A M, BERGAN-DAHL A, et al. Interplay between ryanodine receptor arrangement and function: Implications for (patho)physiological control of calcium release[J]. Circulation Research, 2025, 137(6): 902–923. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.125.325387. [13] QU Zhilin, YAN Dasen, and SONG Zhen. Modeling calcium cycling in the heart: Progress, pitfalls, and challenges[J]. Biomolecules, 2022, 12(11): 1686. doi: 10.3390/biom12111686. [14] PENG Wei, SHEN Huaizong, WU Jianping, et al. Structural basis for the gating mechanism of the type 2 ryanodine receptor RyR2[J]. Science, 2016, 354(6310): aah5324. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5324. [15] LIN Lianyun, WANG Changshi, WANG Wenlan, et al. Cryo-EM structures of ryanodine receptors and diamide insecticides reveal the mechanisms of selectivity and resistance[J]. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1): 9056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-53490-0. [16] DO T Q and KNOLLMANN B C. Inhibitors of intracellular RyR2 calcium release channels as therapeutic agents in arrhythmogenic heart diseases[J]. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2025, 65: 443–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-061724-080739. [17] BORKOĽ, BAUEROVÁ-HLINKOVÁ V, HOSTINOVÁ E, et al. Structural insights into the human RyR2 N-terminal region involved in cardiac arrhythmias[J]. Acta Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography, 2014, 70(11): 2897–2912. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714020343. [18] LAU K and VAN PETEGEM F. Crystal structures of wild type and disease mutant forms of the ryanodine receptor SPRY2 domain[J]. Nature Communications, 2014, 5: 5397. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6397. [19] MEISSNER G. The structural basis of ryanodine receptor ion channel function[J]. Journal of General Physiology, 2017, 149(12): 1065–1089. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711878. [20] LI Pin and CHEN S R W. Molecular basis of Ca2+ activation of the mouse cardiac Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor)[J]. The Journal of General Physiology, 2001, 118(1): 33–44. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.33. [21] WANG Ruiwu, BOLSTAD J, KONG Huihui, et al. The predicted TM10 transmembrane sequence of the cardiac Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) is crucial for channel activation and gating[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2004, 279(5): 3635–3642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311367200. [22] CHI Ximin, GONG Deshun, REN Kang, et al. Molecular basis for allosteric regulation of the type 2 ryanodine receptor channel gating by key modulators[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2019, 116(51): 25575–25582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914451116. [23] XU Le and MEISSNER G. Regulation of cardiac muscle Ca2+ release channel by sarcoplasmic reticulum lumenal Ca2+[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1998, 75(5): 2302–2312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77674-X. [24] CHING L L, WILLIAMS A J, and SITSAPESAN R. Evidence for Ca2+ activation and inactivation sites on the luminal side of the cardiac ryanodine receptor complex[J]. Circulation Research, 2000, 87(3): 201–206. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.3.201. [25] JIANG Dawei, CHEN Wenqian, WANG Ruiwu, et al. Loss of luminal Ca2+ activation in the cardiac ryanodine receptor is associated with ventricular fibrillation and sudden death[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(46): 18309–18314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706573104. [26] LAVER D R and HONEN B N. Luminal Mg2+, a key factor controlling RYR2-mediated Ca2+ release: Cytoplasmic and luminal regulation modeled in a tetrameric channel[J]. The Journal of General Physiology, 2008, 132(4): 429–446. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810001. [27] CHEN Wenqian, WANG Ruiwu, CHEN Biyi, et al. The ryanodine receptor store-sensing gate controls Ca2+ waves and Ca2+-triggered arrhythmias[J]. Nature Medicine, 2014, 20(2): 184–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3440. [28] LAVER D R. Regulation of the RyR channel gating by Ca2+ and Mg2+[J]. Biophysical Reviews, 2018, 10(4): 1087–1095. doi: 10.1007/s12551-018-0433-4. [29] GYÖRKE S and FILL M. Ryanodine receptor adaptation: Control mechanism of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in heart[J]. Science, 1993, 260(5109): 807–809. doi: 10.1126/science.8387229. [30] VALDIVIA H H, KAPLAN J H, ELLIS-DAVIES G C R, et al. Rapid adaptation of cardiac ryanodine receptors: Modulation by Mg2+ and phosphorylation[J]. Science, 1995, 267(5206): 1997–2000. doi: 10.1126/science.7701323. [31] BERS D M. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force[M]. 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Springer, 2001: 198–205. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0658-3. [32] SCHIEFER A, MEISSNER G, and ISENBERG G. Ca2+ activation and Ca2+ inactivation of canine reconstituted cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channels[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 1995, 489(2): 337–348. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021055. [33] FILL M, ZAHRADNÍKOVÁ A, VILLALBA-GALEA C A, et al. Ryanodine receptor adaptation[J]. The Journal of General Physiology, 2000, 116(6): 873–882. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.6.873. [34] DRIES E, GILBERT G, RODERICK H L, et al. The ryanodine receptor microdomain in cardiomyocytes[J]. Cell Calcium, 2023, 114: 102769. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2023.102769. [35] FRANZINI-ARMSTRONG C, PROTASI F, and RAMESH V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca2+ release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1999, 77(3): 1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [36] MALTSEV A V, VENTURA SUBIRACHS V, MONFREDI O, et al. Structure-function relationship of the ryanodine receptor cluster network in sinoatrial node cells[J]. Cells, 2024, 13(22): 1885. doi: 10.3390/cells13221885. [37] NI Haibo, ZHANG Xianwei, WU Yixuan, et al. 3D spatial modeling of sinoatrial node cells reveals a critical role of subcellular ryanodine receptor distribution in pacemaker automaticity[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2023, 122(3): 381a–382a. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.2093. [38] GAO Zhongxue, LI Tiantian, JIANG Hanyu, et al. Calcium oscillation on homogeneous and heterogeneous networks of ryanodine receptor[J]. Physical Review E, 2023, 107(2): 024402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.107.024402. [39] SATO D, GHAYOUMI B, FASOLI A, et al. Positive feedback between RyR phosphorylation and Ca2+ leak promotes heterogeneous Ca2+ release[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2025, 124(5): 717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2025.01.023. [40] LAASMAA M, BRANOVETS J, STOLOVA J, et al. Cardiomyocytes from female compared to male mice have larger ryanodine receptor clusters and higher calcium spark frequency[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2023, 601(18): 4033–4052. doi: 10.1113/JP284515. [41] VERON G, MALTSEV V A, STERN M D, et al. Elementary intracellular Ca signals approximated as a transition of release channel system from a metastable state[J]. Journal of Applied Physics, 2023, 134(12): 124701. doi: 10.1063/5.0151255. [42] CHENG Heping and LEDERER W J. Calcium sparks[J]. Physiological Reviews, 2008, 88(4): 1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [43] NAYAK A R, RANGUBPIT W, WILL A H, et al. Interplay between Mg2+ and Ca2+ at multiple sites of the ryanodine receptor[J]. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1): 4115. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48292-3. [44] REBBECK R T, SVENSSON B, ZHANG Jingyan, et al. Kinetics and mapping of Ca-driven calmodulin conformations on skeletal and cardiac muscle ryanodine receptors[J]. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1): 5120. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48951-5. [45] MARABELLI C, SANTIAGO D J, and PRIORI S G. The Yin and Yang of heartbeats: Magnesium–calcium antagonism is essential for cardiac excitation–contraction coupling[J]. Cells, 2025, 14(16): 1280. doi: 10.3390/cells14161280. [46] LUO C H and RUDY Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes[J]. Circulation Research, 1994, 74(6): 1071–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1071. [47] LIVSHITZ L M and RUDY Y. Regulation of Ca2+ and electrical alternans in cardiac myocytes: Role of CAMKII and repolarizing currents[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2007, 292(6): H2854–H2866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01347.2006. [48] O’HARA T, VIRÁG L, VARRÓ A, et al. Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: Model formulation and experimental validation[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 2011, 7(5): e1002061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002061. [49] CHUDIN E, GOLDHABER J, GARFINKEL A, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and the stability of ventricular tachycardia[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1999, 77(6): 2930–2941. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77126-2. [50] SHIFERAW Y, WATANABE M A, GARFINKEL A, et al. Model of intracellular calcium cycling in ventricular myocytes[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2003, 85(6): 3666–3686. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74784-5. [51] CANNELL M B, KONG C H T, IMTIAZ M S, et al. Control of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release by stochastic RyR gating within a 3D model of the cardiac dyad and importance of induction decay for CICR termination[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2013, 104(10): 2149–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.058. [52] HINCH R, GREENSTEIN J L, TANSKANEN A J, et al. A simplified local control model of calcium-induced calcium release in cardiac ventricular myocytes[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2004, 87(6): 3723–3736. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049973. [53] GREENE D and SHIFERAW Y. Mechanistic link between CaM-RyR2 interactions and the genesis of cardiac arrhythmia[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2021, 120(8): 1469–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.02.016. [54] KEIZER J and LEVINE L. Ryanodine receptor adaptation and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release-dependent Ca2+ oscillations[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1996, 71(6): 3477–3487. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79543-7. [55] STERN M D, SONG Longsheng, CHENG Heping, et al. Local control models of cardiac excitation–contraction coupling: A possible role for allosteric interactions between ryanodine receptors[J]. The Journal of General Physiology, 1999, 113(3): 469–489. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.469. [56] RESTREPO J G, WEISS J N, and KARMA A. Calsequestrin-mediated mechanism for cellular calcium transient alternans[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2008, 95(8): 3767–3789. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130419. [57] ZAHRADNÍKOVÁ A, PAVELKOVÁ J, SABO M, et al. Structure-based mechanism of RyR channel operation by calcium and magnesium ions[J]. PLOS Computational Biology, 2025, 21(4): e1012950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012950. [58] WANG Kai, TU Yuhai, RAPPEL W J, et al. Excitation-contraction coupling gain and cooperativity of the cardiac ryanodine receptor: A modeling approach[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2005, 89(5): 3017–3025. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.058958. [59] GREENE D, LUCHKO T, and SHIFERAW Y. The role of subunit cooperativity on ryanodine receptor 2 calcium signaling[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2023, 122(1): 215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.008. [60] GREENE D, BARTON M, LUCHKO T, et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of the cardiac ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2) gating mechanism[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2022, 126(47): 9790–9809. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c03031. [61] DAL CORTIVO G, BARRACCHIA C G, MARINO V, et al. Alterations in calmodulin-cardiac ryanodine receptor molecular recognition in congenital arrhythmias[J]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2022, 79(2): 127. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04165-w. [62] GUO Tao, GILLESPIE D, and FILL M. Ryanodine receptor current amplitude controls Ca2+ sparks in cardiac muscle[J]. Circulation Research, 2012, 111(1): 28–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265652. [63] WESCOTT A P, JAFRI M S, LEDERER W J, et al. Ryanodine receptor sensitivity governs the stability and synchrony of local calcium release during cardiac excitation-contraction coupling[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2016, 92: 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.024. [64] WU Xu and BERS D M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope are one highly interconnected Ca2+ store throughout cardiac myocyte[J]. Circulation Research, 2006, 99(3): 283–291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233386.02708.72. [65] ZIMA A V, PICHT E, BERS D M, et al. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: Role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion[J]. Circulation Research, 2008, 103(8): E105–E115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.183236. [66] ASAKURA K, CHA C Y, YAMAOKA H, et al. EAD and DAD mechanisms analyzed by developing a new human ventricular cell model[J]. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 2014, 116(1): 11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.08.008. [67] MUKHERJEE S, THOMAS N L, and WILLIAMS A J. A mechanistic description of gating of the human cardiac ryanodine receptor in a regulated minimal environment[J]. Journal of General Physiology, 2012, 140(2): 139–158. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110706. [68] SHANNON T R, WANG Fei, PUGLISI J, et al. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular Myocyte[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2004, 87(5): 3351–3371. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [69] SOBIE E A, DILLY K W, DOS SANTOS CRUZ J, et al. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: An investigative mathematical model of calcium-induced calcium release[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2002, 83(1): 59–78. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75149-7. [70] MALTSEV V A and LAKATTA E G. Numerical models based on a minimal set of sarcolemmal electrogenic proteins and an intracellular Ca2+ clock generate robust, flexible, and energy-efficient cardiac pacemaking[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2013, 59: 181–195. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.004. [71] GRANDI E, PANDIT S V, VOIGT N, et al. Human atrial action potential and Ca2+ model: Sinus rhythm and chronic atrial fibrillation[J]. Circulation Research, 2011, 109(9): 1055–1066. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253955. [72] ALVAREZ-LACALLE E, CANTALAPIEDRA I R, PEÑARANDA A, et al. Dependency of calcium alternans on ryanodine receptor refractoriness[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e55042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055042. [73] TEN TUSSCHER K H W J and PANFILOV A V. Alternans and spiral breakup in a human ventricular tissue model[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2006, 291(3): H1088–H1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00109.2006. [74] RICE J J, SALEET JAFRI M, and WINSLOW R L. Modeling gain and gradedness of Ca2+ release in the functional unit of the cardiac diadic space[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1999, 77(4): 1871–1884. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77030-X. [75] NIVALA M, DE LANGE E, ROVETTI R, et al. Computational modeling and numerical methods for spatiotemporal calcium cycling in ventricular myocytes[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2012, 3: 114. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00114. [76] GURUNG A and GUAN Qingguang. Hybrid PDE-deep neural network model for calcium dynamics in neurons[J]. Journal of Machine Learning for Modeling and Computing, 2025, 6(1): 1–21. doi: 10.1615/JMachLearnModelComput.2024055000. [77] COLMAN M A. RyR cooperativity and mobile buffers: Functional clues to the resolution of the cardiac calcium wave problem?[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2024, 602(24): 6637–6638. doi: 10.1113/JP287762. [78] MONOD J, WYMAN J, and CHANGEUX J P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: A plausible model[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1965, 12(1): 88–118. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80285-6. [79] ZHONG Mingwang and KARMA A. Role of ryanodine receptor cooperativity in Ca2+-wave-mediated triggered activity in cardiomyocytes[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2024, 602(24): 6745–6787. doi: 10.1113/JP286145. [80] VIDAL-LIMON A, AGUILAR-TOALÁ J E, and LICEAGA A M. Integration of molecular docking analysis and molecular dynamics simulations for studying food proteins and bioactive peptides[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2022, 70(4): 934–943. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c06110. [81] NEUBERGEROVÁ M and PLESKOT R. Plant protein–lipid interfaces studied by molecular dynamics simulations[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2024, 75(17): 5237–5250. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erae228. [82] ZHOU Chaogang, LI Jinyue, WANG Shuhuan, et al. Development of molecular dynamics and research progress in the study of slag[J]. Materials, 2023, 16(15): 5373. doi: 10.3390/ma16155373. [83] MOSKVIN A S. The electron-conformational model of ryanodine receptors of the heart cell[J]. Technical Physics, 2018, 63(9): 1277–1287. doi: 10.1134/S1063784218090128. [84] DI FRANCESCO D and NOBLE D. A model of cardiac electrical activity incorporating ionic pumps and concentration changes[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 1985, 307(1133): 353–398. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1985.0001. [85] STERN M D. Theory of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle[J]. Biophysical Journal, 1992, 63(2): 497–517. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81615-6. [86] GREENSTEIN J L and WINSLOW R L. An integrative model of the cardiac ventricular myocyte incorporating local control of Ca2+ release[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2002, 83(6): 2918–2945. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75301-0. [87] HAKE J, EDWARDS A G, YU Zeyun, et al. Modelling cardiac calcium sparks in a three-dimensional reconstruction of a calcium release unit[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2012, 590(18): 4403–4422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.227926. [88] NIVALA M, KO C Y, NIVALA M, et al. Criticality in intracellular calcium signaling in cardiac myocytes[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2012, 102(11): 2433–2442. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.001. [89] SONG Zhen, LIU M B, and QU Zhilin. Transverse tubular network structures in the genesis of intracellular calcium alternans and triggered activity in cardiac cells[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2018, 114: 288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.12.003. [90] DONALD L and LAKATTA E G. What makes the sinoatrial node tick? A question not for the faint of heart[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2023, 378(1879): 20220180. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0180. [91] MALTSEV V A and LAKATTA E G. The funny current in the context of the coupled-clock pacemaker cell system[J]. Heart Rhythm, 2012, 9(2): 302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.09.022. [92] MALTSEV V A and LAKATTA E G. Synergism of coupled subsarcolemmal Ca2+ clocks and sarcolemmal voltage clocks confers robust and flexible pacemaker function in a novel pacemaker cell model[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2009, 296(3): H594–H615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01118.2008. [93] SEVERI S, FANTINI M, CHARAWI L A, et al. An updated computational model of rabbit sinoatrial action potential to investigate the mechanisms of heart rate modulation[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2012, 590(18): 4483–4499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229435. [94] STERN M D, MALTSEVA L A, JUHASZOVA M, et al. Hierarchical clustering of ryanodine receptors enables emergence of a calcium clock in sinoatrial node cells[J]. Journal of General Physiology, 2014, 143(5): 577–604. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311123. [95] HEIJMAN J, ERFANIAN ABDOUST P, VOIGT N, et al. Computational models of atrial cellular electrophysiology and calcium handling, and their role in atrial fibrillation[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2016, 594(3): 537–553. doi: 10.1113/JP271404. [96] SUTANTO H, VAN SLOUN B, SCHÖNLEITNER P, et al. The subcellular distribution of ryanodine receptors and L-type Ca2+ channels modulates Ca2+-transient properties and spontaneous Ca2+-release events in atrial cardiomyocytes[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2018, 9: 1108. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01108. [97] VAGOS M R, AREVALO H, HEIJMAN J, et al. A novel computational model of the rabbit atrial cardiomyocyte with spatial calcium dynamics[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2020, 11: 556156. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.556156. [98] ZHANG Xianwei, WU Yixuan, SMITH C E R, et al. Enhanced Ca2+-driven arrhythmogenic events in female patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from computational modeling[J]. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology, 2024, 10(11): 2371–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2024.07.020. [99] ZHANG Xianwei, NI Haibo, MOROTTI S, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous Ca2+ release-mediated arrhythmia in a novel 3D human atrial myocyte model: I. Transverse-axial tubule variation[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2023, 601(13): 2655–2683. doi: 10.1113/JP283363. [100] ZHANG Xianwei, SMITH C E R, MOROTTI S, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous Ca2+ release-mediated arrhythmia in a novel 3D human atrial myocyte model: II. Ca2+-handling protein variation[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2023, 601(13): 2685–2710. doi: 10.1113/JP283602. [101] HANCOX J C, YUILL K H, MITCHESON J S, et al. Progress and gaps in understanding the electrophysiological properties of morphologically normal cells from the cardiac atrioventricular node[J]. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, 2003, 13(12): 3675–3691. doi: 10.1142/S021812740300879X. [102] LIU Yaning, ZENG Wanzhen, DELMAR M, et al. Ionic mechanisms of electronic inhibition and concealed conduction in rabbit atrioventricular nodal myocytes[J]. Circulation, 1993, 88(4): 1634–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.4.1634. [103] JACKOWSKA-ZDUNIAK B and FORYŚ U. Mathematical model of the atrioventricular nodal double response tachycardia and double-fire pathology[J]. Mathematical Biosciences & Engineering, 2016, 13(6): 1143–1158. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2016035. [104] INADA S, HANCOX J C, ZHANG Henggui, et al. One-dimensional mathematical model of the atrioventricular node including atrio-nodal, nodal, and nodal-his cells[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2009, 97(8): 2117–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.056. [105] CHENG Hongwei, LI Jue, JAMES A F, et al. Characterization and influence of cardiac background sodium current in the atrioventricular node[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2016, 97: 114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.04.014. [106] TERRAR D A. Timing mechanisms to control heart rhythm and initiate arrhythmias: Roles for intracellular organelles, signalling pathways and subsarcolemmal Ca2+[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2023, 378(1879): 20220170. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0170. [107] SHI Shuqing, ZHANG Xiaohan, LV Jiayu, et al. Multi-omics reveals mechanism of Qi-Po-Sheng-Mai granule in reducing atrial fibrillation susceptibility in aged rats[J]. Chinese Medicine, 2025, 20(1): 118. doi: 10.1186/s13020-025-01154-6. [108] HE B J, BOYDEN P, and SCHEINMAN M. Ventricular arrhythmias involving the His-Purkinje system in the structurally abnormal heart[J]. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2018, 41(9): 1051–1059. doi: 10.1111/pace.13465. [109] LIMBU B, SHAH K, WEINBERG S H, et al. Role of cytosolic calcium diffusion in murine cardiac Purkinje cells[J]. Clinical Medicine Insights: Cardiology, 2016, 10(S1): 17–26. doi: 10.4137/CMC.S39705. [110] VAIDYANATHAN R, O’CONNELL R P, DEO M, et al. The ionic bases of the action potential in isolated mouse cardiac Purkinje cell[J]. Heart Rhythm, 2013, 10(1): 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.10.002. [111] LI Pan and RUDY Y. A model of canine Purkinje cell electrophysiology and Ca2+ cycling: Rate dependence, triggered activity, and comparison to ventricular myocytes[J]. Circulation Research, 2011, 109(1): 71–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246512. [112] SHAH C, JIWANI S, LIMBU B, et al. Delayed afterdepolarization-induced triggered activity in cardiac purkinje cells mediated through cytosolic calcium diffusion waves[J]. Physiological Reports, 2019, 7(24): e14296. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14296. [113] SHOU Jian and HUO Yunlong. Changes of calcium cycling in HFrEF and HFpEF[J]. Mechanobiology in Medicine, 2023, 1(1): 100001. doi: 10.1016/j.mbm.2023.100001. [114] NEGRONI J. A cardiac muscle model relating sarcomere dynamics to calcium kinetics[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 1996, 28(5): 915–929. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0086. [115] RICE J J, WINSLOW R L, and HUNTER W C. Comparison of putative cooperative mechanisms in cardiac muscle: Length dependence and dynamic responses[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 1999, 276(5): H1734–H1754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1734. [116] JI Y C, GRAY R A, and FENTON F H. Implementation of contraction to electrophysiological ventricular myocyte models, and their quantitative characterization via post-extrasystolic potentiation[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0135699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135699. [117] GYÖRKE S, BELEVYCH A E, LIU Bin, et al. The role of luminal Ca regulation in Ca signaling refractoriness and cardiac arrhythmogenesis[J]. Journal of General Physiology, 2017, 149(9): 877–888. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711808. [118] KAPLAN A D, BOYMAN L, WARD C W, et al. Ryanodine receptor stabilization therapy suppresses Ca2+-based arrhythmias in a novel model of metabolic HFpEF[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2024, 195: 68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2024.07.006. [119] LI Xiaoqian, WU Meiqiong, FANG Lihua, et al. Cardiac FGF23 increases intracellular calcium in atrial myocytes and the susceptibility to atrial fibrillation decreased in FGF23f/fMYHCCre/+ mice[J]. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2025, 29(6): e70517. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.70517. [120] FOWLER E D and ZISSIMOPOULOS S. Molecular, subcellular, and arrhythmogenic mechanisms in genetic RyR2 disease[J]. Biomolecules, 2022, 12(8): 1030. doi: 10.3390/biom12081030. [121] SONG Zhen, QU Zhilin, and KARMA A. Stochastic initiation and termination of calcium-mediated triggered activity in cardiac myocytes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2017, 114(3): E270–E279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614051114. [122] FANG Lihua, CHEN Qian, CHENG Xianlu, et al. Calcium-mediated DAD in membrane potentials and triggered activity in atrial myocytes of ETV1f/fMyHCCre/+ mice[J]. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2024, 28(16): e70005. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.70005. [123] VENETUCCI L A, TRAFFORD A W, and EISNER D A. Increasing ryanodine receptor open probability alone does not produce arrhythmogenic calcium waves: Threshold sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is required[J]. Circulation Research, 2007, 100(1): 105–111. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252828.17939.00. [124] CONNELL P, WORD T A, and WEHRENS X H T. Targeting pathological leak of ryanodine receptors: Preclinical progress and the potential impact on treatments for cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure[J]. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 2020, 24(1): 25–36. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1708326. [125] JIANG Dawei, XIAO Bailong, YANG Dongmei, et al. RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death reduce the threshold for store-overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR)[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(35): 13062–13067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402388101. [126] BELEVYCH A E, TERENTYEV D, TERENTYEVA R, et al. Shortened Ca2+ signaling refractoriness underlies cellular arrhythmogenesis in a postinfarction model of sudden cardiac death[J]. Circulation Research, 2012, 110(4): 569–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260455. [127] SONG Zhen, KO C Y, NIVALA M, et al. Calcium-voltage coupling in the genesis of early and delayed afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2015, 108(8): 1908–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.011. [128] QU Zhilin, XIE Laihua, OLCESE R, et al. Early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes: Beyond reduced repolarization reserve[J]. Cardiovascular Research, 2013, 99(1): 6–15. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt104. [129] ZHAO Yanting, VALDIVIA C R, GURROLA G B, et al. Arrhythmogenesis in a catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia mutation that depresses ryanodine receptor function[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(13): E1669–E1677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419795112. [130] ZHONG Mingwang, REES C M, TERENTYEV D, et al. NCX-mediated subcellular Ca2+ dynamics underlying early afterdepolarizations in LQT2 cardiomyocytes[J]. Biophysical Journal, 2018, 115(6): 1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.004. [131] SVENSSON B, NITU F R, REBBECK R T, et al. Molecular mechanism of a FRET biosensor for the cardiac ryanodine receptor pathologically leaky state[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(16): 12547. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612547. [132] WEHRENS X H T, LEHNART S E, REIKEN S R, et al. Protection from cardiac arrhythmia through ryanodine receptor-stabilizing protein Calstabin2[J]. Science, 2004, 304(5668): 292–296. doi: 10.1126/science.1094301. [133] GEORGE S A, BRENNAN-MCLEAN J A, TRAMPEL K A, et al. Ryanodine receptor inhibition with acute dantrolene treatment reduces arrhythmia susceptibility in human hearts[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2023, 325(4): H720–H728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00103.2023. [134] MCCAULEY M D and WEHRENS X H T. Targeting ryanodine receptors for anti-arrhythmic therapy[J]. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 2011, 32(6): 749–757. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.44. [135] KIRIYAMA K, KIYOSUE T, WANG J C, et al. Effects of JTV-519, a novel anti-ischaemic drug, on the delayed rectifier K+ current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes[J]. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 2000, 361(6): 646–653. doi: 10.1007/s002100000230. [136] ISHIDA R, ZENG Xi, KUREBAYASHI N, et al. Discovery and structure–activity relationship of a ryanodine receptor 2 inhibitor[J]. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2024, 72(4): 399–407. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c24-00114. [137] YANG Peichi, MORENO J D, MIYAKE C Y, et al. In silico prediction of drug therapy in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2016, 594(3): 567–593. doi: 10.1113/JP271282. [138] YANG Peichi, BELARDINELLI L, and CLANCY C E. Mechanisms of chemical atrial defibrillation by flecainide and ibutilide[J]. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology, 2024, 10(12): 2658–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2024.08.009. [139] LV Tingting, LI Siyuan, LI Qing, et al. The role of RyR2 mutations in congenital heart diseases: Insights into cardiac electrophysiological mechanisms[J]. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology, 2025, 36(3): 683–692. doi: 10.1111/jce.16569. [140] KEEFE J A, MOORE O M, HO K S, et al. Role of Ca2+ in healthy and pathologic cardiac function: From normal excitation–contraction coupling to mutations that cause inherited arrhythmia[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2023, 97(1): 73–92. doi: 10.1007/s00204-022-03385-0. [141] FOWLER E D, DIAKITE S L, GOMEZ A M, et al. Disruption of ventricular activation by subthreshold delayed afterdepolarizations in RyR2-R420Q catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia[J]. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology Plus, 2025, 13: 100466. doi: 10.1016/j.jmccpl.2025.100466. [142] KHERA R, OIKONOMOU E K, NADKARNI G N, et al. Transforming cardiovascular care with artificial intelligence: From discovery to practice: JACC state-of-the-art review[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2024, 84(1): 97–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.05.003. [143] SHIFERAW K B, WALI P, WALTEMATH D, et al. Navigating the AI frontiers in cardiovascular research: A bibliometric exploration and topic modeling[J]. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2024, 10: 1308668. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1308668. [144] VANDENBERK B, CHEW D S, PRASANA D, et al. Successes and challenges of artificial intelligence in cardiology[J]. Frontiers in Digital Health, 2023, 5: 1201392. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1201392. [145] SAHLI COSTABAL F, YANG Yibo, PERDIKARIS P, et al. Physics-informed neural networks for cardiac activation mapping[J]. Frontiers in Physics, 2020, 8: 42. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.00042. [146] HERRERO MARTIN C, OVED A, CHOWDHURY R A, et al. EP-PINNs: Cardiac electrophysiology characterisation using physics-informed neural networks[J]. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022, 8: 768419. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.768419. [147] QIAN Shuang, UGURLU D, FAIRWEATHER E, et al. Developing cardiac digital twin populations powered by machine learning provides electrophysiological insights in conduction and repolarization[J]. Nature Cardiovascular Research, 2025, 4(5): 624–636. doi: 10.1038/s44161-025-00650-0. [148] CAMPS J, WANG Z J, DOSTE R, et al. Cardiac digital twin pipeline for virtual therapy evaluation[Z]. arXiv: 2401.10029, 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.10029. (查阅网上资料,请核对文献类型及格式是否正确). [149] TOMEK J, NIEVES-CINTRON M, NAVEDO M F, et al. SparkMaster 2: A new software for automatic analysis of calcium spark data[J]. Circulation Research, 2023, 133(6): 450–462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.322847. -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: