Visible Figure Part of Multi-source Maritime Ship Dataset

-

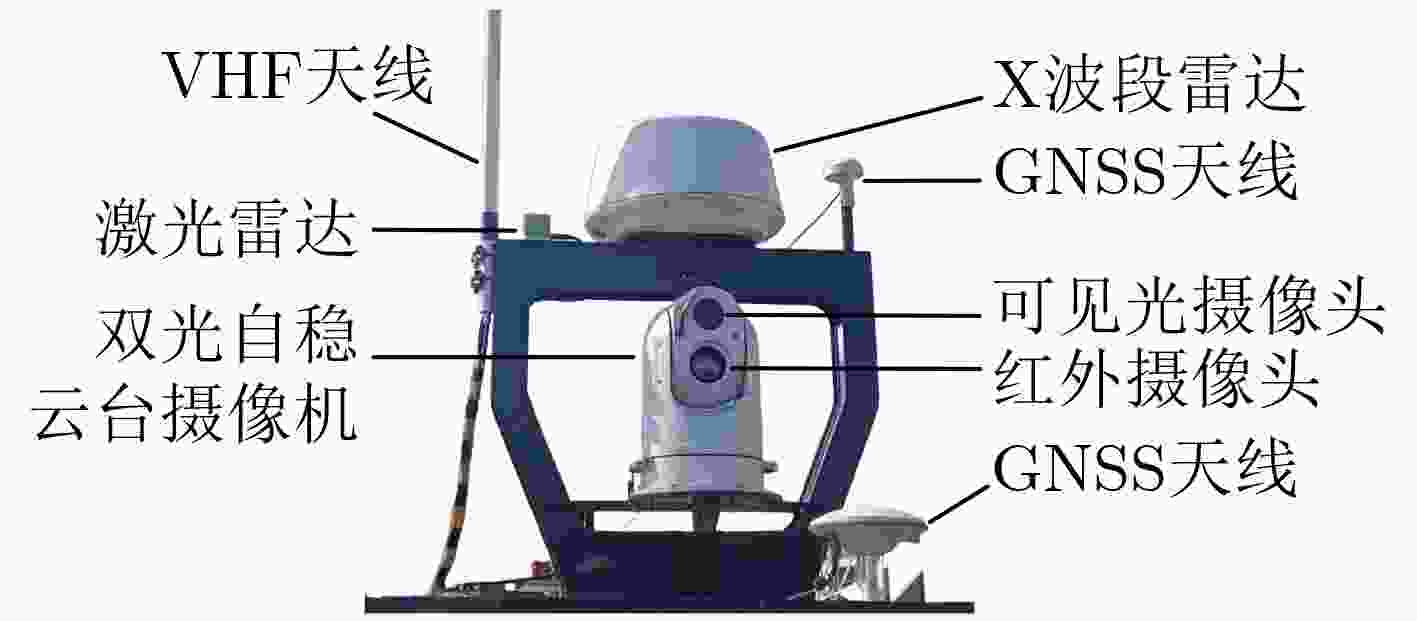

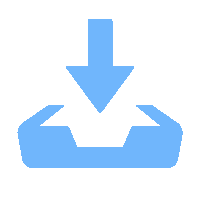

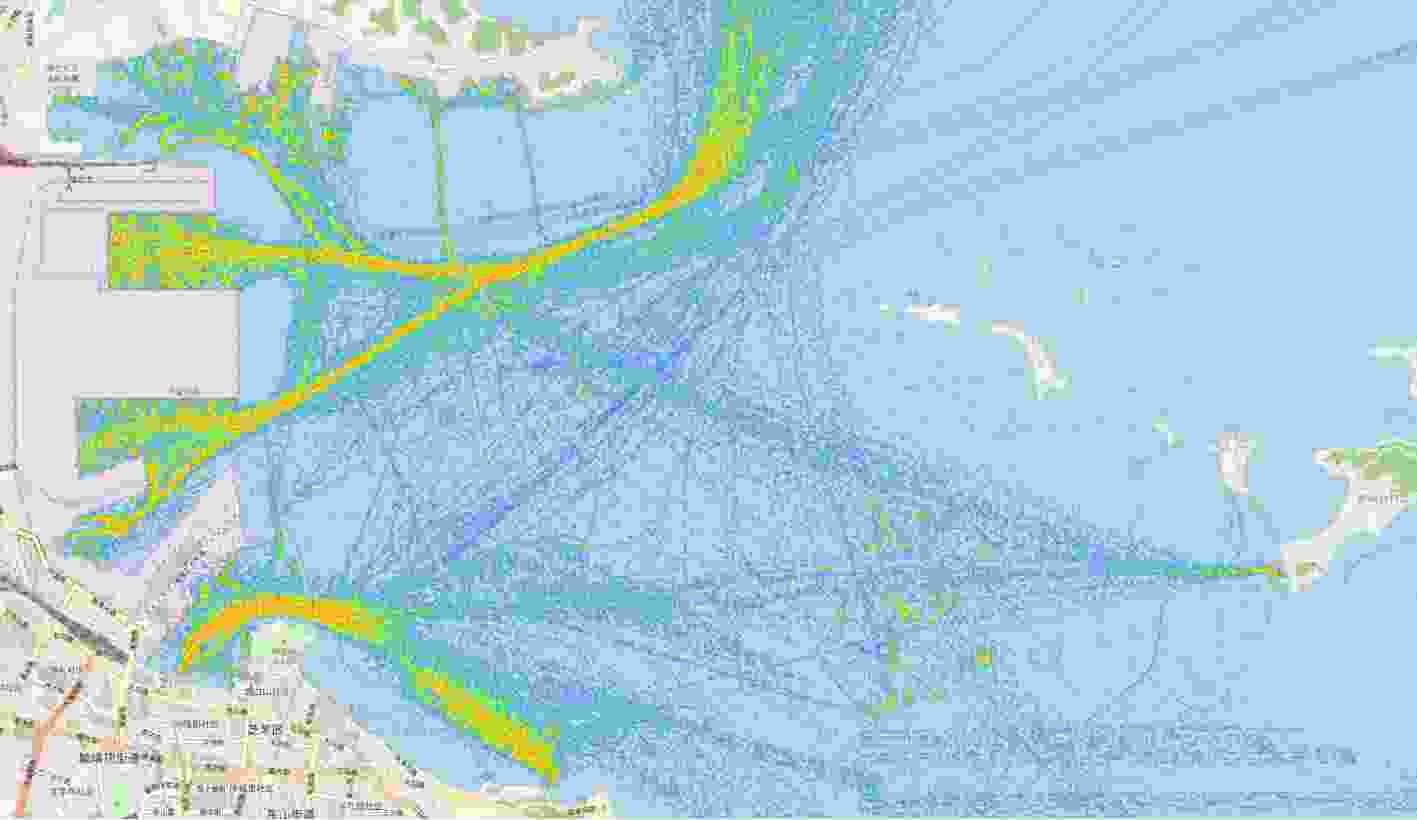

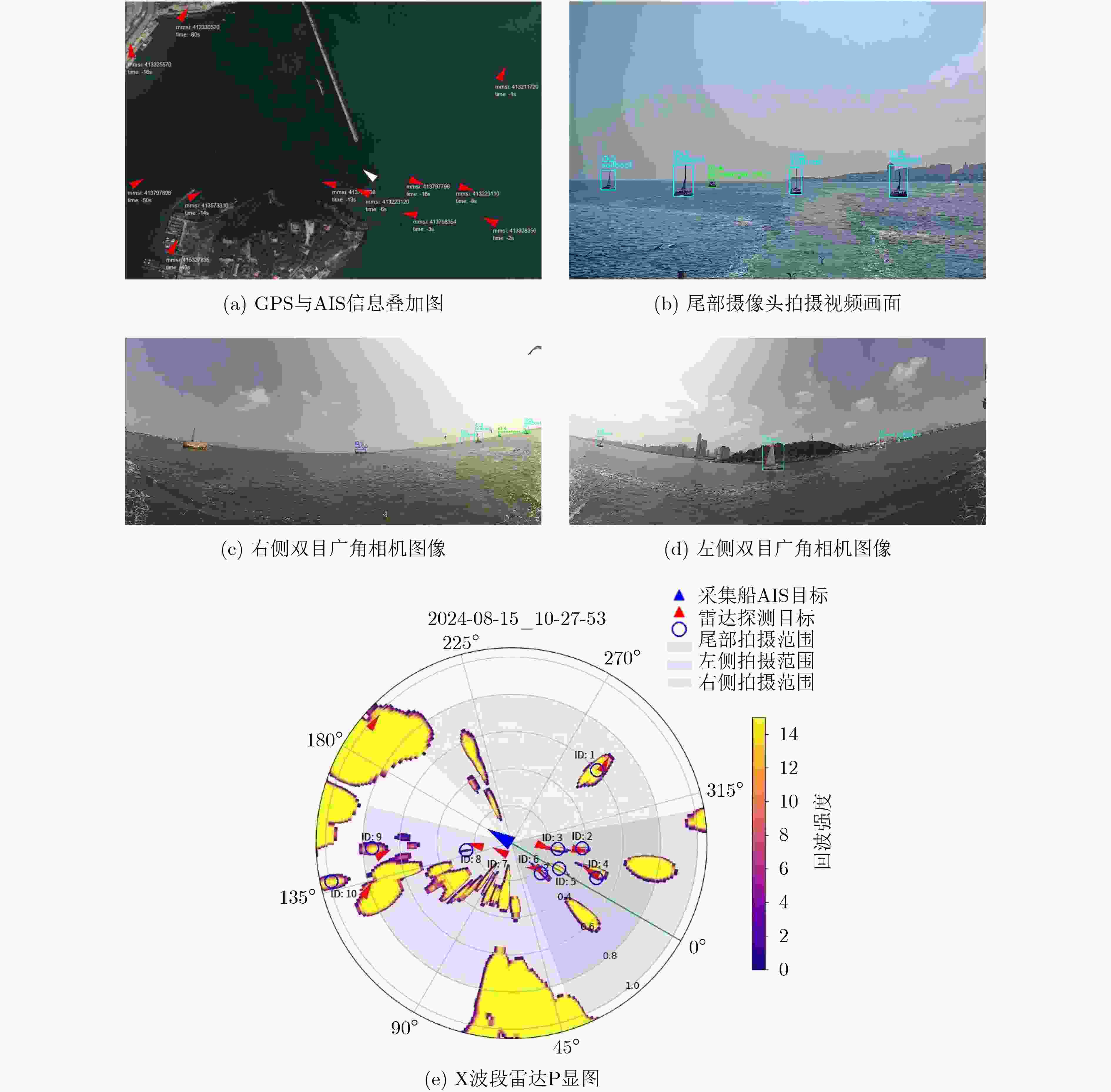

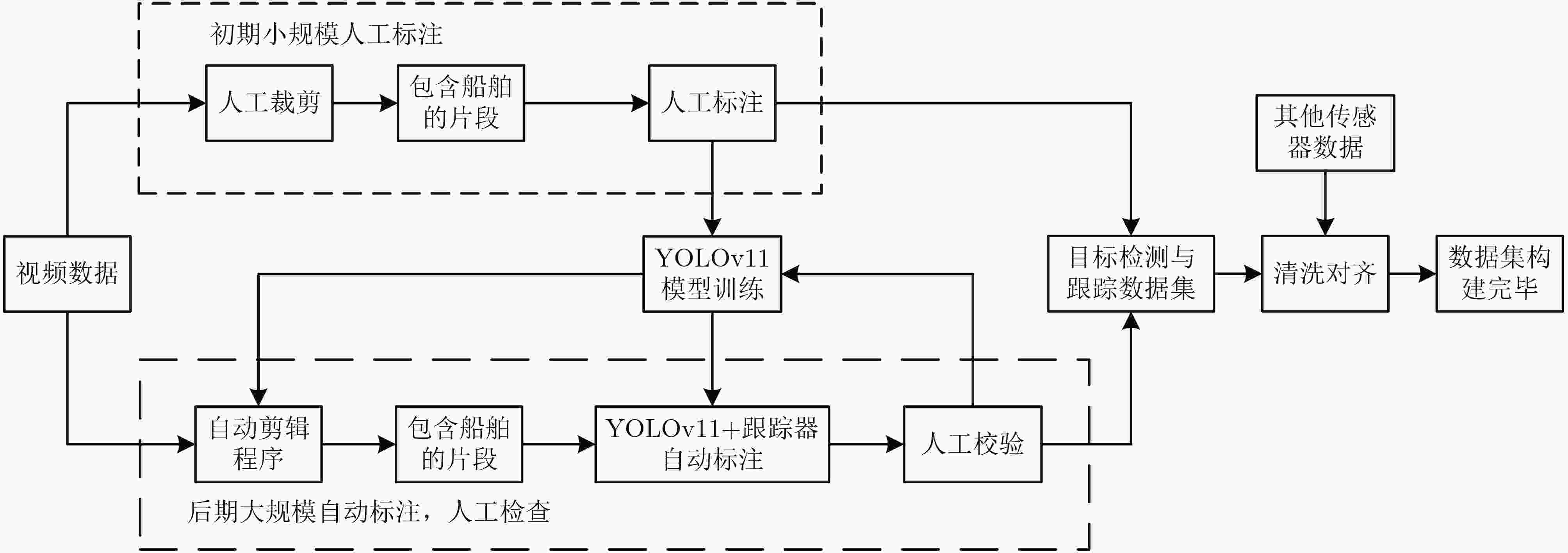

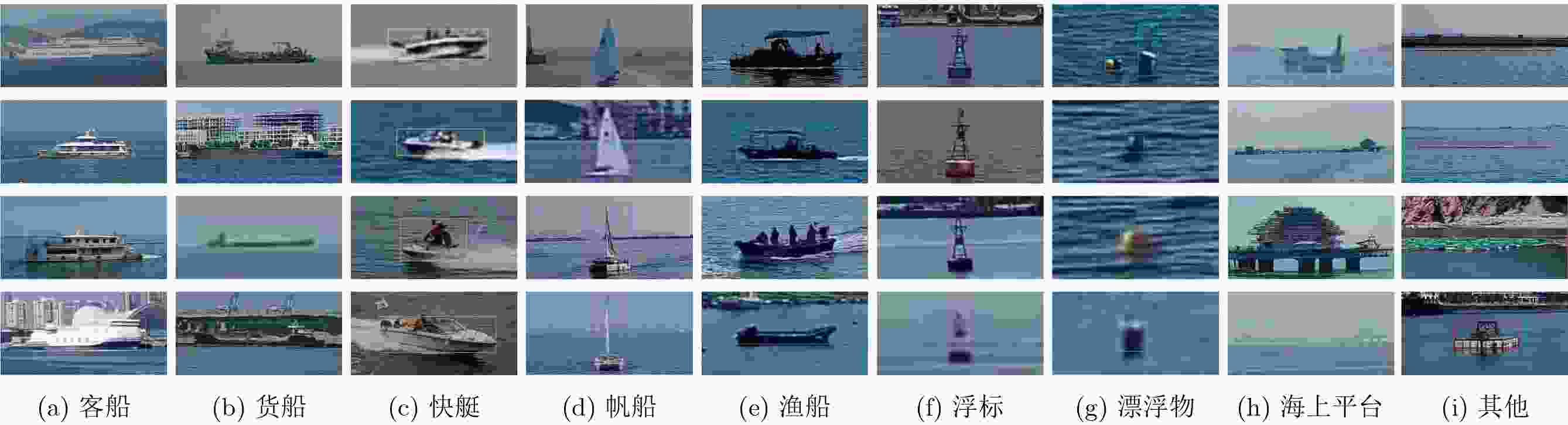

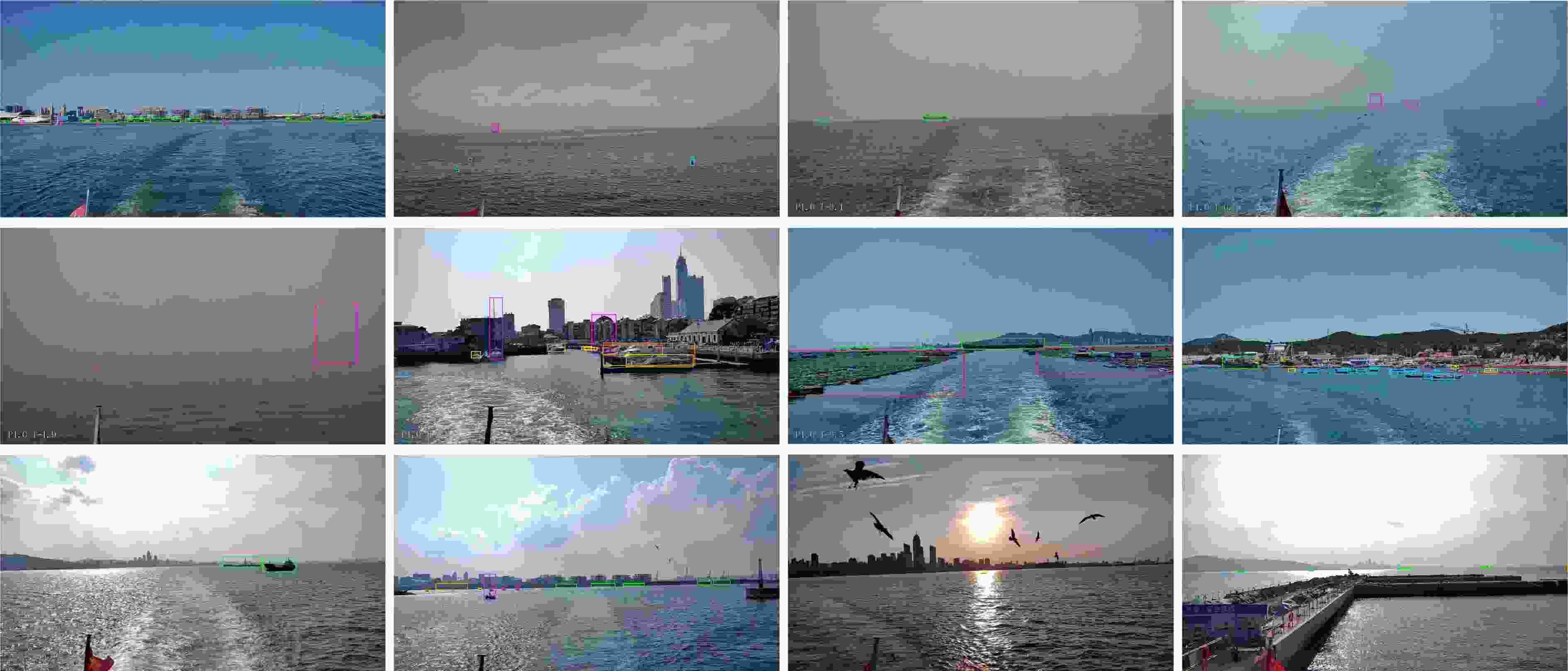

摘要: 为适应海上船只目标智能感知发展趋势,针对现有海上船只目标感知数据集信源单一、船只目标类别少、场景简单等问题,该文研制了由雷达、可见光、红外、激光、AIS和GPS等传感器构成的海上目标集成采集设备,开展了近2个月船载海上观测实验,累计时长达到200小时,收集海上多源原始数据90 TB;进一步对海量数据进行处理标注,并针对所采集原始数据海量、价值密度低的问题,设计了一套自动标注与人工校验相结合的数据快速标注流程,经多次智能标注模型训练与大量人工校验,目前已构建海上船只目标多源数据集的可见光图像部分(MSMS-VF)。该数据集涵盖客船、货船、快艇、帆船、渔船、浮标、漂浮物及海上平台等9种目标类别,包含265,233张图像,1,097,268个边界标注框,小目标占比达到55.88%,覆盖了多样化的海洋目标环境,可为目标检测、目标识别、目标跟踪等智能算法研究提供训练测试数据原料。未来,团队将陆续发布数据集的其他部分,并结合新的观测实验,对数据集进行不断更新。

-

关键词:

- 海上船只目标感知 /

- 海上船只大规模数据集 /

- 小目标检测 /

- 深度学习

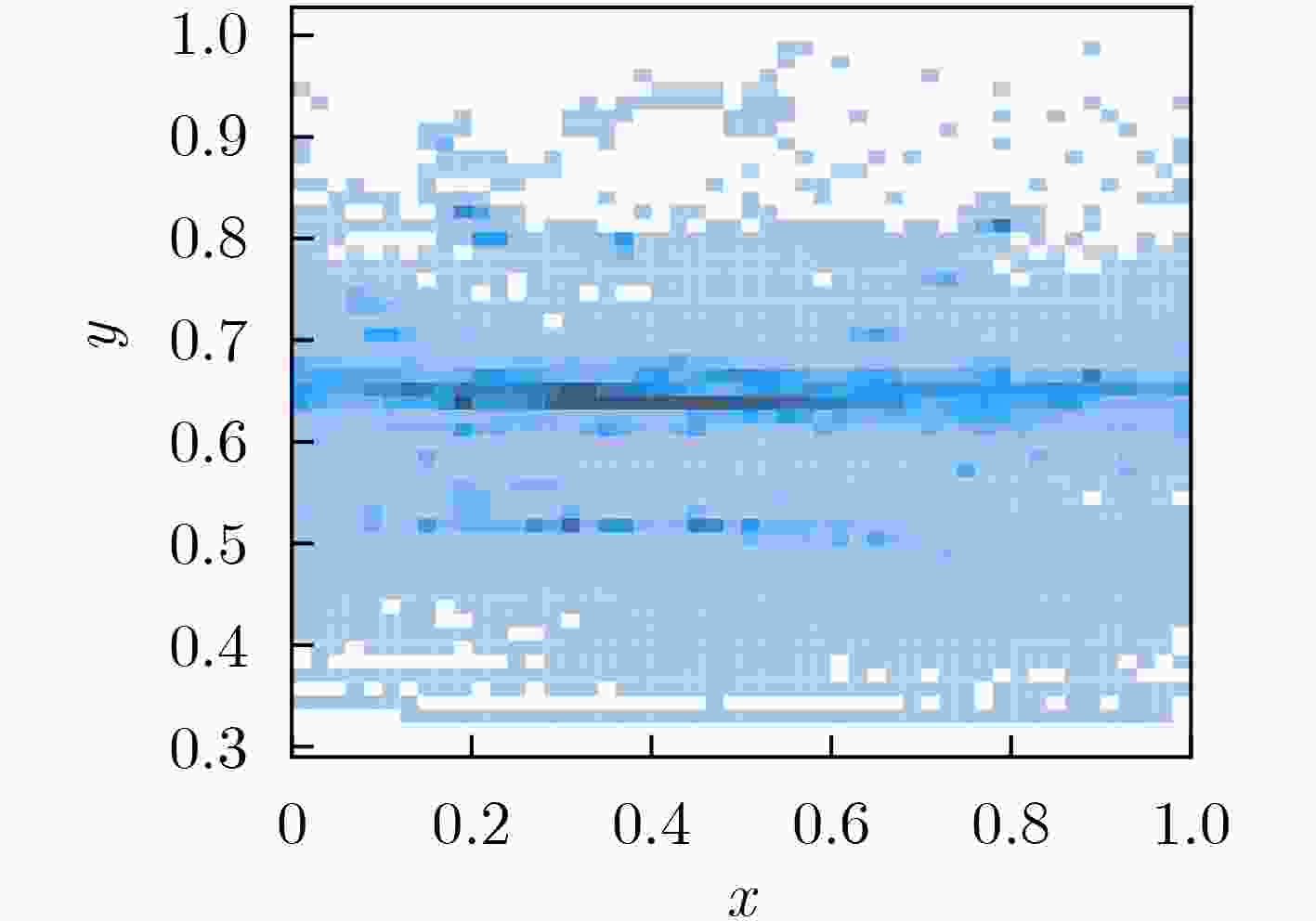

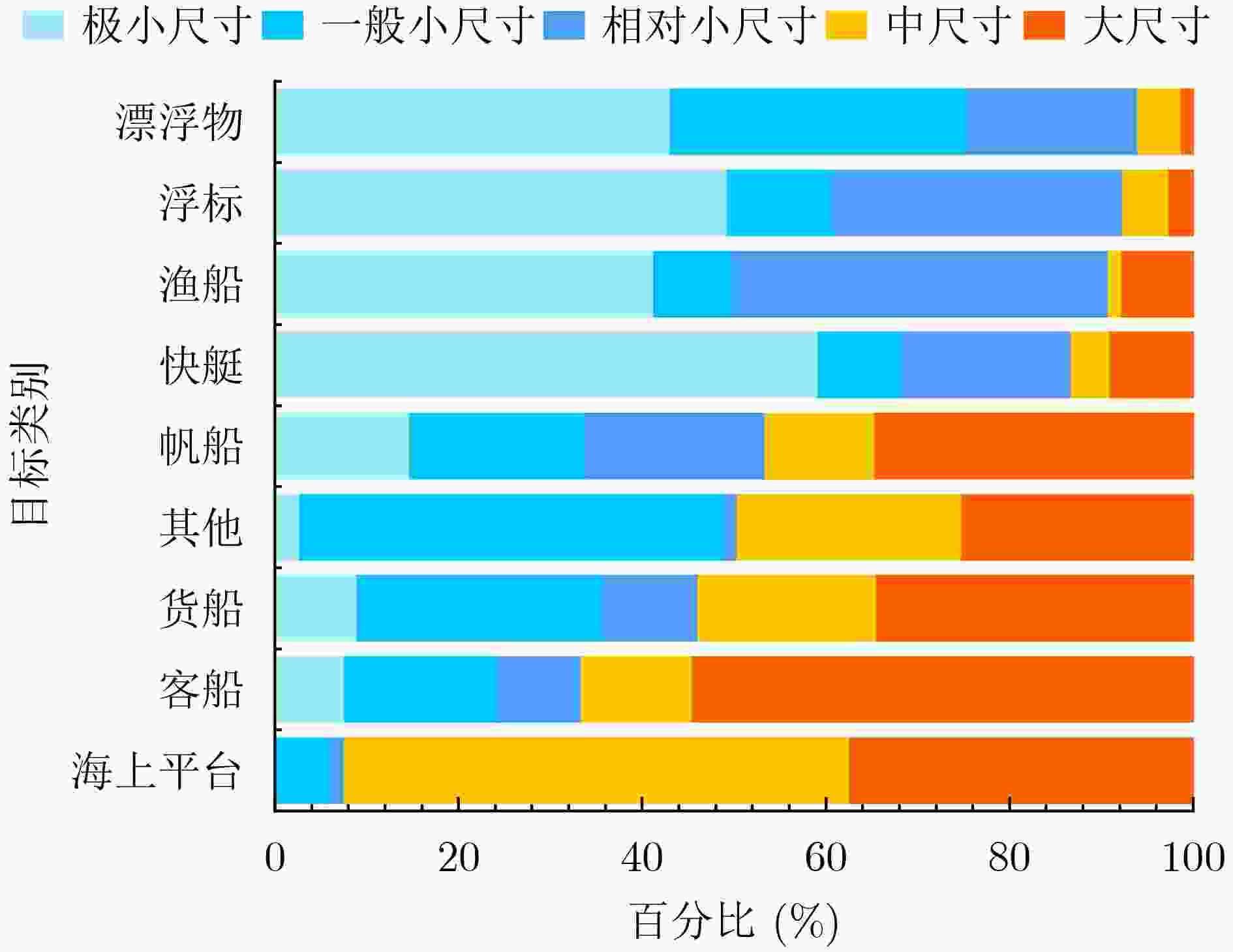

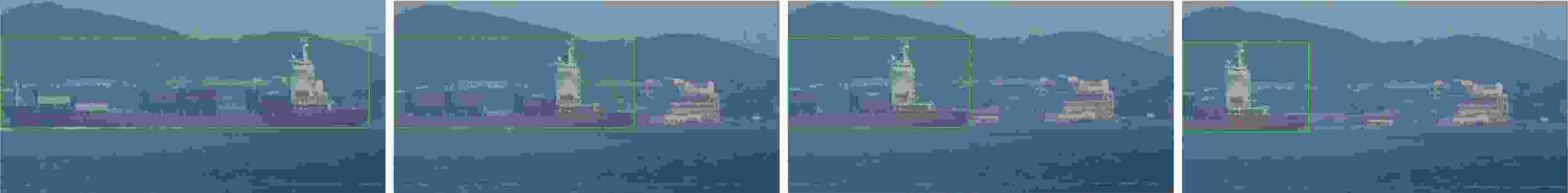

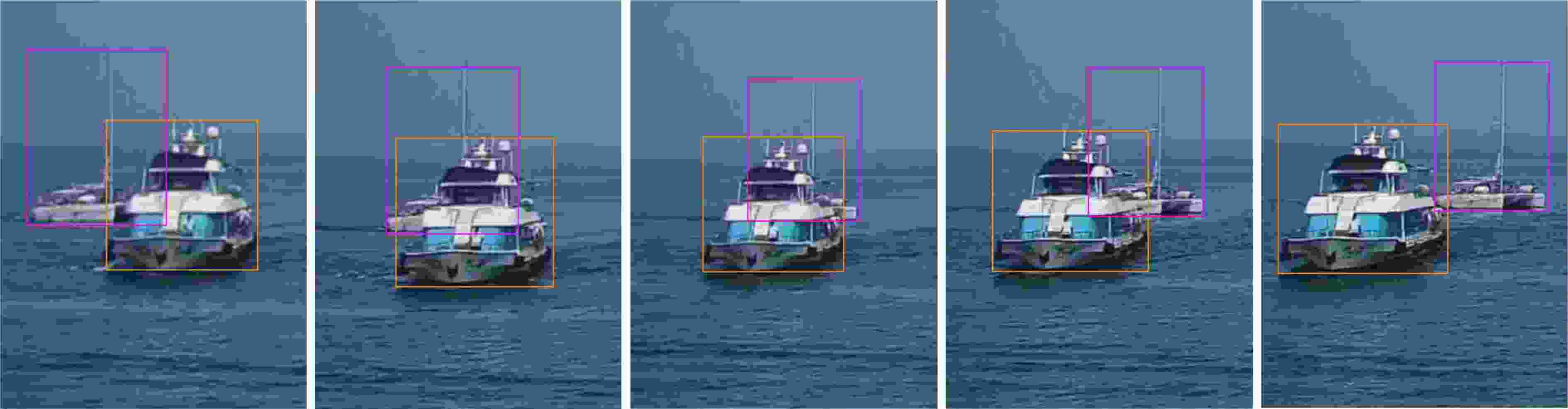

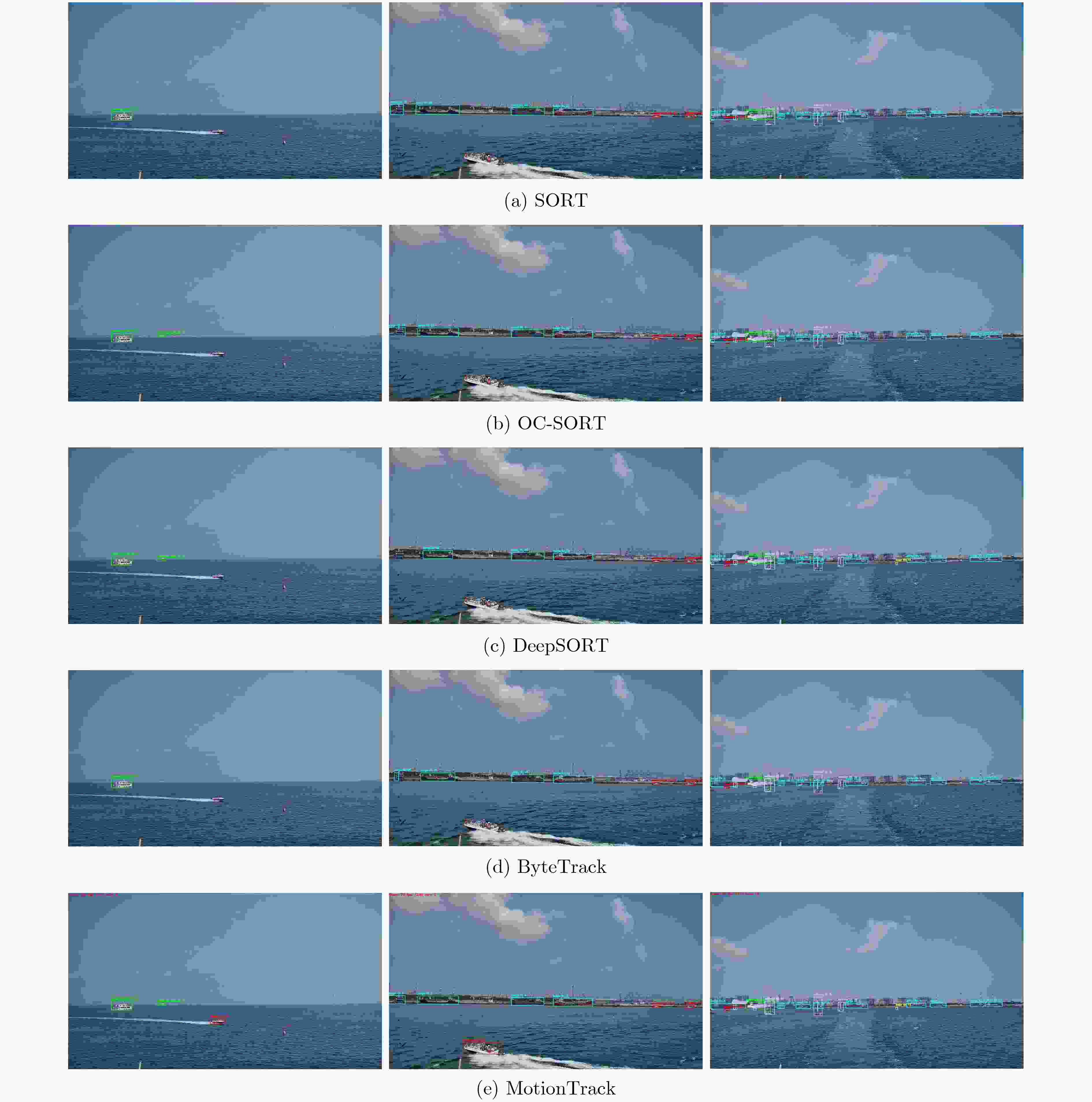

Abstract:Objective The increasing intensity of marine resource development and maritime operations has heightened the need for accurate vessel detection under complex marine conditions, which is essential for protecting maritime rights and interests. In recent years, object detection algorithms based on deep learning—such as YOLO and Faster R-CNN—have emerged as key methods for maritime target perception due to their strong feature extraction capabilities. However, their performance relies heavily on large-scale, high-quality training data. Existing general-purpose datasets, such as COCO and PASCAL VOC, offer limited vessel classes and predominantly feature static, urban, or terrestrial scenes, making them unsuitable for marine environments. Similarly, specialized datasets like SeaShips and the Singapore Marine Dataset (SMD) suffer from constraints such as limited data sources, simple scenes, small sample sizes, and incomplete coverage of marine target categories. These limitations significantly hinder further performance improvement of detection algorithms. Therefore, the development of large-scale, multimodal, and comprehensive marine-specific datasets represents a critical step toward resolving current application challenges. This effort is urgently needed to strengthen marine monitoring capabilities and ensure operational safety at sea. Methods To overcome the aforementioned challenges, a multi-sensor marine target acquisition system integrating radar, visible-light, infrared, laser, Automatic Identification System (AIS), and Global Positioning System (GPS) technologies is developed. A two-month shipborne observation campaign is conducted, yielding 200 hours of maritime monitoring and over 90 TB of multimodal raw data. To efficiently process this large volume of low-value-density data, a rapid annotation pipeline is designed, combining automated labeling with manual verification. Iterative training of intelligent annotation models, supplemented by extensive manual correction, enables the construction of the Visible Figure Part of the Multi-Source Maritime Ship Dataset (MSMS-VF). This dataset comprises 265 233 visible-light images with 1 097 268 bounding boxes across nine target categories: passenger ship, cargo vessel, speedboat, sailboat, fishing boat, buoy, floater, offshore platform, and others. Notably, 55.88% of targets are small, with pixel areas below 1 024. The dataset incorporates diverse environmental conditions including backlighting, haze, rain, and occlusion, and spans representative maritime settings such as harbor basins, open seas, and navigation channels. MSMS-VF offers a comprehensive data foundation for advancing maritime target detection, recognition, and tracking research. Results and Discussions The MSMS-VF dataset exhibits substantially greater diversity than existing datasets ( Table 1 ,Table 2 ). Small targets, including buoys and floaters, occur frequently (Table 5 ), posing significant challenges for detection. Five object detection models—YOLO series, Real-Time Detection Transformer (RT-DETR), Faster R-CNN, Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD), and RetinaNet—are assessed, together with five multi-object tracking algorithms: Simple Online and Realtime Tracking (SORT), Optimal Compute for SORT (OC-SORT), DeepSORT, ByteTrack, and MotionTrack. YOLO models exhibit the most favorable trade-off between speed and accuracy. YOLOv11 achieves a mAP50 of 0.838 on the test set and a processing speed of 34.43 fps (Table 6 ). However, substantial performance gaps remain for small targets; for instance, YOLOv11 yields a mAP50 of 0.549 for speedboats, markedly lower than the 0.946 obtained for large targets such as cargo vessels (Table 7 ). RT-DETR shows moderate performance on small objects, achieving a mAP50 of 0.532 for floaters, whereas conventional models like Faster R-CNN perform poorly, with mAP50 values below 0.1. For tracking, MotionTrack performs best under low-frame-rate conditions, achieving a MOTA of 0.606, IDF1 of 0.750, and S of 0.681 using a Gaussian distance cascade-matching strategy (Table 8 ,Fig. 13 ).Conclusions This study presents the MSMS-VF dataset, which offers essential data support for maritime perception research through its integration of multi-source inputs, diverse environmental scenarios, and a high proportion of small targets. Experimental validation confirms the dataset’s utility in training and evaluating state-of-the-art algorithms, while also revealing persistent challenges in detecting and tracking small objects under dynamic maritime conditions. Nevertheless, the dataset has limitations. The current data are predominantly sourced from waters near Yantai, leading to imbalanced ship-type representation and the absence of certain vessel categories. Future efforts will focus on expanding data acquisition to additional maritime regions, broadening the scope of multi-source data collection, and incrementally releasing extended components of the dataset to support ongoing research. -

表 1 通用目标检测数据集概览

表 2 船舶目标检测数据集

表 3 海上目标分类及标注框数量

目标类别 数量 描述 客船 95, 109 客船、游船、渡轮等中大型船舶 货船 335, 687 货船、工程船、拖船等多种大型船舶 快艇 212, 413 快艇、摩托艇、皮划艇等小型船舶 渔船 22, 230 渔船、钓鱼船等中小型船舶 帆船 224, 511 帆船等利用风力航行的船舶 浮标 65, 349 航标等航道标志物 漂浮物 118, 110 浮球等海面漂浮物 海上平台 19, 561 光伏平台、海洋牧场等海上作业平台 其他 4, 298 管道型浮排、养殖区等其他目标 表 4 标注属性

目标像素

尺寸天气情况 目标显示

比例是否被

遮挡光照情况 目标背景

属性小尺寸 晴天 全部 无遮挡 良好 海面背景 中尺寸 雨天 部分 遮挡 逆光 复杂背景 大尺寸 雾霾 — — — — 表 5 目标尺寸等级分布

尺寸等级 小尺寸 中尺寸 大尺寸 极小尺寸 相对小尺寸 一般小尺寸 像素面积范围 0~144 144~400 400~ 1024 1024 ~2048>2048 标注框数量 195,753 201,569 215,805 153,354 330,787 占比(%) 17.84 18.37 19.67 13.98 30.14 表 6 各目标检测模型整体评估结果

模型 主干网络 输入分辨率 评估数据集 P R F1 mAP50 mAP50-95 fps YOLOv5[26] CSPDarknet 640×640 val 0.959 0.764 0.850 0.829 0.560 32.74 test 0.954 0.779 0.858 0.829 0.561 YOLOv8[27] YOLOv8s 640×640 val 0.918 0.755 0.829 0.837 0.590 35.36 test 0.936 0.745 0.830 0.833 0.599 YOLOv11[28] YOLOv11s 640×640 val 0.929 0.759 0.835 0.841 0.592 34.43 test 0.930 0.76 0.836 0.838 0.604 RT-DETR[6] Resnet50 800×800 val 0.694 0.625 0.657 0.664 0.356 28.25 test 0.690 0.628 0.658 0.665 0.356 Faster-RNN[7] Vgg16 600×600 val 0.695 0.381 0.470 0.224 0.139 18.21 test 0.694 0.388 0.480 0.221 0.138 Faster-RNN[7] Resnet50 600×600 val 0.606 0.408 0.47 0.255 0.142 16.81 test 0.594 0.425 0.48 0.243 0.140 SSD[24] Vgg16 300×300 val 0.877 0.365 0.49 0.508 0.218 15.41 test 0.877 0.374 0.500 0.503 0.223 SSD[24] mobilenetv2 300×300 val 0.703 0.374 0.490 0.346 0.123 21.88 test 0.695 0.371 0.480 0.343 0.127 RestinaNet[25] Resnet50 600×600 val 0.990 0.213 0.340 0.118 0.079 14.85 test 0.994 0.220 0.34 0.119 0.081 表 7 各目标检测模型在不同类别目标的评估结果

目标检测

模型评估数据集 mAP50 客船 货船 快艇 渔船 帆船 浮标 漂浮物 海上平台 其他 YOLOv5[26]

(CSPDarknet)val 0.948 0.944 0.547 0.649 0.884 0.744 0.829 0.983 0.934 test 0.951 0.947 0.554 0.645 0.885 0.752 0.819 0.951 0.914 YOLOv8[27]

(YOLOv8s)val 0.953 0.940 0.535 0.723 0.889 0.706 0.826 0.993 0.968 test 0.958 0.943 0.541 0.689 0.888 0.713 0.829 0.994 0.941 YOLOv11[28]

(YOLOv11)val 0.959 0.943 0.542 0.727 0.887 0.717 0.833 0.994 0.971 test 0.964 0.946 0.549 0.706 0.889 0.720 0.832 0.995 0.937 RT-DETR[6]

(Resnet50)val 0.872 0.859 0.379 0.420 0.715 0.403 0.533 0.926 0.871 test 0.874 0.864 0.383 0.416 0.731 0.416 0.532 0.928 0.836 Faster-RNN[7]

(Vgg16)val 0.588 0.318 0.070 0.061 0.441 0.044 0.044 0.235 0.197 test 0.594 0.322 0.072 0.054 0.441 0.039 0.040 0.256 0.171 Faster-RNN[7]

(Resnet50)val 0.607 0.386 0.079 0.071 0.446 0.048 0.039 0.289 0.325 test 0.627 0.388 0.080 0.061 0.455 0.040 0.037 0.317 0.317 SSD[24]

(Vgg16)val 0.795 0.736 0.230 0.361 0.557 0.190 0.268 0.881 0.820 test 0.807 0.746 0.217 0.343 0.552 0.192 0.256 0.895 0.803 SSD[24]

(mobilenetv2)val 0.617 0.466 0.117 0.220 0.367 0.101 0.190 0.594 0.618 test 0.623 0.473 0.116 0.225 0.370 0.106 0.196 0.603 0.549 RetinaNet[25]

(Resnet50)val 0.375 0.176 0.036 0.018 0.280 0.008 0.004 0.087 0.042 test 0.387 0.173 0.038 0.021 0.275 0.006 0.006 0.102 0.022 表 8 各目标跟踪算法整体评估结果

表 9 各目标跟踪算法对于不同类别目标的评估结果

跟踪算法 Si 客船 货船 快艇 帆船 浮标 漂浮物 海上平台 其他 SORT[29] 0.904 0.757 0.134 0.659 0.462 0.608 0.885 0.695 OC-SORT[30] 0.906 0.779 0.148 0.692 0.496 0.614 0.921 0.691 DeepSORT[31] 0.900 0.776 0.157 0.729 0.555 0.611 0.903 0.679 ByteTrack[32] 0.909 0.783 0.125 0.689 0.495 0.628 0.945 0.823 MotionTrack[33] 0.942 0.812 0.238 0.742 0.580 0.590 0.940 0.840 -

[1] PERERA L P, OLIVEIRA P, and SOARES C G. Maritime traffic monitoring based on vessel detection, tracking, state estimation, and trajectory prediction[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2012, 13(3): 1188–1200. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2012.2187282. [2] LIU Yand, AN Bailin, CHEN Shaohua, et al. Multi‐target detection and tracking of shallow marine organisms based on improved YOLO v5 and DeepSORT[J]. IET Image Processing, 2024, 18(9): 2273–2290. doi: 10.1049/ipr2.13090. [3] LIU Zhixiang, ZHANG Youmin, YU Xiang, et al. Unmanned surface vehicles: An overview of developments and challenges[J]. Annual Reviews in Control, 2016, 41: 71–93. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2016.04.018. [4] 尹宏鹏, 陈波, 柴毅, 等. 基于视觉的目标检测与跟踪综述[J]. 自动化学报, 2016, 42(10): 1466–1489. doi: 10.16383/j.aas.2016.c150823.YIN Hongpeng, CHEN Bo, CHAI Yi, et al. Vision-based object detection and tracking: A review[J]. Acta Automatica Sinica, 2016, 42(10): 1466–1489. doi: 10.16383/j.aas.2016.c150823. [5] REDMON J, DIVVALA S, GIRSHICK R, et al. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection[C]. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, USA, 2016: 779–788. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [6] ZHAO Yian, LV Wenyu, XU Shangliang, et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection[C]. 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, USA, 2024: 16965–16974. doi: 10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01605. [7] REN Shaoqing, HE Kaiming, GIRSHICK R, et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks[J]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2017, 39(6): 1137–1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [8] JIANG Zhikai, SU Li, and SUN Yixin. YOLOv7-ship: A lightweight algorithm for ship object detection in complex marine environments[J]. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2024, 12(1): 190. doi: 10.3390/jmse12010190. [9] FAN Xiyu, HU Zhuhua, ZHAO Yaochi, et al. A small-ship object detection method for satellite remote sensing data[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2024, 17: 11886–11898. doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3419786. [10] YANG Defu, SOLIHIN M I, ARDIYANTO I, et al. Author correction: A streamlined approach for intelligent ship object detection using EL-YOLO algorithm[J]. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1): 19408. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70017-1. [11] GUO Yiran, SHEN Qiang, AI Danni, et al. Sea-IoUTracker: A more stable and reliable maritime target tracking scheme for unmanned vessel platforms[J]. Ocean Engineering, 2024, 299: 117243. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117243. [12] LIN T Y, MAIRE M, BELONGIE S, et al. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context[C]. The 13th European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 2014: 740–755. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48. [13] EVERINGHAM M, VAN GOOL L, WILLIAMS C K I, et al. The pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) challenge[J]. International Journal of Computer Vision, 2010, 88(2): 303–338. doi: 10.1007/s11263-009-0275-4. [14] DENG Jia, DONG Wei, SOCHER R, et al. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database[C]. 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, USA, 2009: 248–255. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [15] KUZNETSOVA A, ROM H, ALLDRIN N, et al. The open images dataset V4: Unified image classification, object detection, and visual relationship detection at scale[J]. International Journal of Computer Vision, 2020, 128(7): 1956–1981. doi: 10.1007/S11263-020-01316-Z. [16] SHAO Zhenfeng, WU Wenjing, WANG Zhongyuan, et al. SeaShips: A large-scale precisely-annotated dataset for ship detection[J]. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 2018, 20(10): 2593–2604. doi: 10.1109/TMM.2018.2865686. [17] PRASAD D K, RAJAN D, RACHMAWATI L, et al. Video processing from electro-optical sensors for object detection and tracking in a maritime environment: A survey[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2017, 18(8): 1993–2016. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2016.2634580. [18] IANCU B, SOLOVIEV V, ZELIOLI L, et al. ABOships—an inshore and offshore maritime vessel detection dataset with precise annotations[J]. Remote Sensing, 2021, 13(5): 988. doi: 10.3390/rs13050988. [19] HE Boyong, LI Xianjiang, HUANG Bo, et al. UnityShip: A large-scale synthetic dataset for ship recognition in aerial images[J]. Remote Sensing, 2021, 13(24): 4999. doi: 10.3390/rs13244999. [20] ZHENG Yitong and ZHANG Shun. Mcships: A large-scale ship dataset for detection and fine-grained categorization in the wild[C]. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), London, UK, 2020: 1–6. doi: 10.1109/ICME46284.2020.9102907. [21] NANDA A, CHO S W, LEE H, et al. KOLOMVERSE: Korea open large-scale image dataset for object detection in the maritime universe[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2024, 25(12): 20832–20840. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2024.3449122. [22] 何友, 周伟. 海上信息感知大数据技术[J]. 指挥信息系统与技术, 2018, 9(2): 1–7. doi: 10.15908/j.cnki.cist.2018.02.001.HE You and ZHOU Wei. Big data technology for maritime information sensing[J]. Command Information System and Technology, 2018, 9(2): 1–7. doi: 10.15908/j.cnki.cist.2018.02.001. [23] CHENG Gong, YUAN Xiang, and YAO Xiwen, et al. Towards large-scale small object detection: Survey and benchmarks[J]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023, 45(11): 13467–13488. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3290594. [24] LIU Wei, ANGUELOV D, ERHAN D, et al. SSD: Single shot MultiBox detector[C]. The 14th European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016: 21–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [25] LIN T Y, GOYAL P, GIRSHICK R, et al. Focal loss for dense object detection[J]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2020, 42(2): 318–327. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2858826. [26] JOCHER G, CHAURASIA A, STOKEN A, et al. Ultralytics/yolov5: V6.1-TensorRT, TensorFlow edge TPU and OpenVINO export and inference[J]. Zenodo, 2022. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6222936. [27] AKYON F C. Yolov8.3. 62[EB/OL]. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics/releases/tag/v8.3.62, 2024. [28] KHANAM R and HUSSAIN M. YOLOv11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements[EB/OL]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.17725, 2024. [29] BEWLEY A, GE Zongyuan, OTT L, et al. Simple online and realtime tracking[C]. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, USA, 2016: 3464–3468. doi: 10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533003. [30] CAO Jinkun, PANG Jiangmiao, WENG Xinshuo, et al. Observation-centric SORT: Rethinking SORT for robust multi-object tracking[C]. 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, Canada, 2023: 9686–9696. doi: 10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00934. [31] WOJKE N, BEWLEY A, and PAULUS D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric[C]. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 2017: 3645–3649. doi: 10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296962. [32] ZHANG Yifu, SUN Peize, JIANG Yi, et al. ByteTrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box[C]. The 17th European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 2022: 1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-20047-2_1. [33] 肖刚, 梁振起, 曾柳, 等. 基于高斯距离匹配的海面多目标跟踪方法及系统[P]. 中国, 202211457200.0, 2023.XIAO Gang, LIANG Zhenqi, ZENG Liu, et al. Sea surface multi-target tracking method and system based on Gaussian distance matching[P]. China, 202211457200.0, 2023. -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: